I’m currently reworking my PhD thesis into a book. I knew that this process would not be easy (I’ve read the books about writing The Book). But no one said it would be painful.

I mean this partly in jest. My monograph is about the inimitable Margery Kempe, from a medical perspective, and the painful experience of her spiritual journey. But puns aside, not only has it been inestimably difficult to stand back critically from the PhD thesis that I feel that I literally gave birth to, but to attempt to pin down somehow what we mean by ‘pain’ – in the medieval or modern context – is an even more painful challenge.

I’ve explored modern medical definitions of pain, scales of pain, and theories like Gate Control; the literary-cultural work of Elaine Scarry, more recent historiographical work by Joanna Bourke, and Javier Moscoso, and work on pain by medievalists like Esther Cohen and Ariel Glucklich. And more…

While this work has forced me to address important questions – is pain just a physical sensation? Is there such a thing as emotional pain? Spiritual pain? Is pain culturally-constructed? Is suffering the same as pain? Or maybe a variation thereof? Is pain an “it”? Does it exist in essence? Or is it always referential, even metaphorical?

We frequently describe pain in terms of metaphors, like stabbing, pricking, piercing, throbbing…

But how else do we speak of it?

While Scarry’s ground-breaking book has shaped many of our perspectives on pain, she has been criticised for her assumption that some sort of Platonic-Pain-Ideal exists, in her emphasis on its ineffability. Joanna Bourke’s suggestion that pain is “an event” holds much appeal in this respect. That it is not some abstract or unreachably true phenomenon, but something that happens to us. Something that we experience, over a brief – or extended – period of time. Pain must surely be defined not only in terms of its perceived intensity, but its temporal, or chronic, extent. Alicia Spencer-Hall’s recent work and reading forum on chronic pain has been illuminating, here.

Inevitably, it has been impossible to separate my own painful experiences from this endeavour. Apart from a frightening accident last year involving heavy Victorian furniture, concussion, a lacerated head and face, an ambulance, shock, A&E, and a plastic surgeon; two rounds of childbirth are probably the most memorable.

In fact, memory, I think, has a crucial part to play in thinking about pain. While my accident last year was incredibly serious, and I will never forget being carried to my bed by the paramedics so they could staunch the bleeding and assess my vitals (my body was in such shock by this point that my limbs were convulsing and my pulse double the normal rate), I now look back on the “event” almost as an objective onlooker, and marvel at my body’s instinctive mechanisms in the face of injury, and threat of death. I took daily photographs of my stitched wounds and rainbow-bruises, posting them on social media, narrating the visual progress of my healing.

Why did I do this? I don’t know. Maybe I needed external validation of my pain and injuries. Maybe I subconsciously wanted to share what was, to be frank, flipping hurting.

Similarly (although admittedly with more joyous ends), my memories of childbirth, now 12 and 9 years ago, tell different stories.

Childbirth #1 took eleven hours and, probably because of my youthful anxiety and fear – an epidural – was ultimately low on pain (eventually).

Childbirth #2 took two and a half hours. We barely made it to hospital, and I gave birth with just a few gasps of Gas and Air and some decidedly unladylike grunts. I’ll never forget the intensity of that pain. I felt in another world; on another plane of consciousness; acceptingly on the brink of life and death.

But which experience was preferable? More rewarding? More exhilarating?

#2.

It is a time-honoured saying that if women didn’t somehow ‘forget’ the pain of childbirth, there would be no more second babies in the world.

But do we forget? Or do we re-interpret?

There is no denying that Childbirth #2 was the most painful, existential experience of my life. But that’s the one I’d repeat.

Why? Because it was quick. Because I felt what it was really like to give birth to a human being. Because we could leave the hospital almost straight away. Because I felt a sense of achievement – elation, even – at making it through to the other side. Much of the research on the gendering of pain suggests that women’s pain is culturally associated with suffering and sacrifice, and men’s pain with heroicism and battle.

But I felt like a warrior that day. That I’d “done it”. I’d conquered the painful legacy of Eve. Is this why I’d choose a more painful experience over a lesser (different) one? Does this make me more, or less, female?

I’m not sure that I’ll ever know the answer. Or whether it even matters. But how does all this play into my book revisions?

Kempe uses the term pain or its derivatives – peyne, payn, peyne – over eighty times in her Book. Beyond this, she speaks of angwisch, disease, and labowr. She applies the term fluidly. Sometimes she describes the tribulations of sickness and affliction. Sometimes the pain of Christ on the cross. Sometimes Mary’s pain at grieving for her son. And sometimes her own pain at losing her spiritual zest, or being excluded from the religious rituals that sustain her, or losing her affective tears, or losing Christ himself. She writes into her text what pain means, for her, in those contexts.

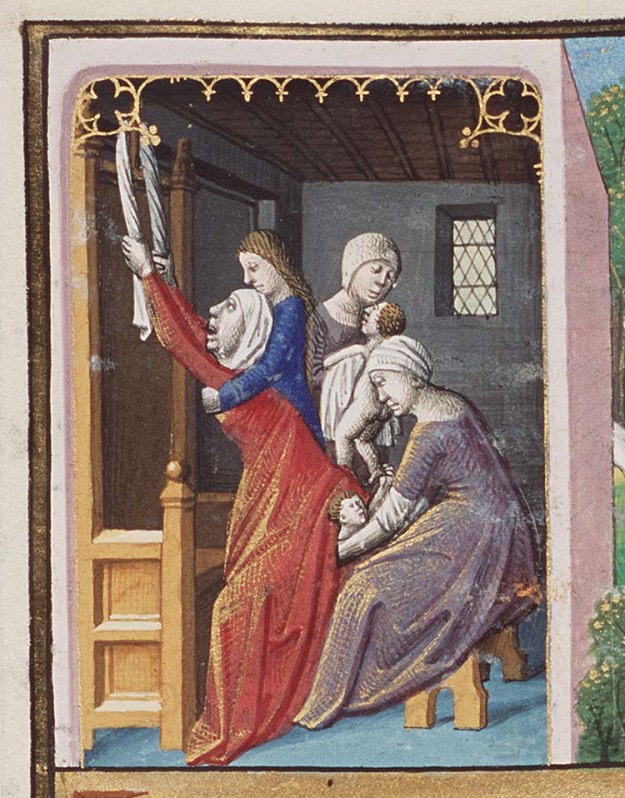

Despite giving birth fourteen times, only one childbirth experience – her first – is described in The Book of Margery Kempe. Frequently analysed by scholars, it is perhaps the most violent, urgent, and terrifying episode in the text. The birth did not go well. Fearing she would die, a priest was called to give Kempe the last rites. But he did not allow her to confess fully, and this emotional anguish, combined with the inevitable physical pain of her ruptured, postpartum body, caused her to go owt of hir mende for over eight months. Nearly annihilated, both by a difficult childbirth and by being silenced before she could secure her spiritual future, Kempe’s only option was to temporarily vacate her body: to leave herself.

The Middle English Dictionary defines “peine” with different priorities to our modern understanding. 1a) is the action of punishing, punishment; execution; that which is imposed or suffered in punishment. 1b) is a fine, an amercemen. 1c) is in phrases expressing legal or official penalties or threats: “under peines”. 2a) is physical torture inflicted upon someone in persecution, imprisonment; suffering endured in penance or mortification; to die by torture; the pains or agony suffered by Christ. 3) is the punishment or suffering that souls endure after death, in purgatory or hell; also, an instance or form of such torment. 4) is physical pain in bodily parts or wounds; illness; the agony or throes physical discomfort; the pain of giving birth; an experience of physical discomfort. 5) is mental or emotional suffering, grief, distress, anxiety. 6) is misfortune, adversity, trouble, hardship; danger; perils; a wretched condition or circumstance.

Notice that the physical sensation of pain, or illness, does not occur until the fourth denotation. Hardship or adversity occurs at the sixth denotation. In the medieval vernacular, pain had more immediate associations with punishment, torture and penance.

So when Kempe describes an emotional or spiritual experience as ‘painful’, then (for example, when she is excluded from Mass), does she mean for us to understand that it hurts her in the physical sense?

Is she hurting in a torturous sense?

I cannot help but think that modern society is returning to similar medieval medical understandings of the body-mind-divide as porous. Recent research into mindfulness, for example, indicates that this is the case.

I remember (as ‘pain events’ seem to demand) a news story about a woman who lost her entire family in the Indonesian tsunami of 2004. Having lost a husband and two children in an instant, she described how the grief was so painful that it hurt, viscerally, so much, that she took paracetamol in an attempt to ease the sensation.

Pain, for this broken woman, saw no distinction between body and mind. The sensation was the same. It hurt.

So, while I grapple with the lexical and ontological underpinnings of my book, I might not reach a definitive conclusion of what pain is. That’s because it is more than one thing. And the memory of pain has profound repercussions for how we describe it. This must play into the dictation of the Margery Kempe’s Book during her older age. And like Kempe’s Book, ‘pain’ will be written into my text just as it is written into hers, becoming embodied in a different way.

This ‘Wound Man’, from an early 15th century medical miscellany, has the text literally written into his abdomen. Designed to direct physicians towards the correct section of the text, the writing becomes a part of his body: the injured body and text converge.

I may not reach a singular definition of pain, but I think, like Kempe, that I can describe it, and therefore know it.

And also to show how, perhaps unexpectedly, that medieval and modern thinking about the messy vicissitudes of suffering, is painfully close.

Another excellent article, please keep them coming.

LikeLike

Very interesting; thank you. You might find Elizabeth Spelman’s “Fruits of Sorrow” helpful . . .

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Clarissa. I shall get hold of the book.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love this. I’m not a medievalist but I teach anthologized excerpts of Margery’s BOOK almost every year, most recently a few weeks ago. One of the things this class got into was the language MK had to deploy to describe that pain and the outbursts that follow, and the way she so often has to turn to audience reactions as a way of showing their skepticism, which the project of writing is supposed to counter. I always wish I had more time to teach her, but it’s always the context of broad survey courses. It’s such a necessary window into the existence of a medieval woman.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Andy! That’s kind of you. I’m glad that you have found teaching MK fruitful. I certainly have a soft spot for her, and students of course love (or hate!) her. She was a brave woman who was unapologetic about her emotive style of devotion – as you say, a very interesting example of a medieval woman’s life.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My take on the love/hate (aka ick factor): https://oldestvocation.wordpress.com/2015/02/24/this-creature-40-years-of-margery-kempe/

LikeLiked by 1 person